| The Dispersal and Resettlement of the Oak Lake Metis to 1900 |

by Gerhard J. Ens, Department of History and Classics, University of Alberta

Few western-Canadian communities or groups have been studied in as much detail as the Red River Metis. This has produced both a wealth of knowledge about the Plains Metis that settled at Red River, and a certain "Red River Myopia" that regards all western Metis as variants of the Red River type or products of the same dynamics. Those Metis communities, even those that were closely connected to the Red River Metis, but which had a different history, have been largely ignored despite the fact their stories would help us to understand the Red River story better. For example, the Metis of the Oak Lake/Grande Clairiere locale, located in southwestern Manitoba, lived in and utilized the resources of this region for a long period of time, albeit in two different and quite distinct periods. The history of these two occupations, in a sense reverses the chronology of the history of the Red River Settlement. As such, the resettlement of the Oak Lake Metis provides a corrective, or at least a complexity, to the usual story of the dispersal of the Metis from Manitoba. As part of a larger settlement of the Oak Lake area by Quebecois, French, and Belgian Francophone Catholics, this story also provides some insight into the decline of a Metis identity in a small Manitoba community where French, as much as Anglo-Canadian, settlers undercut and submerged a Metis identity.

Metis utilization of this area has been examined in some detail by archaeologists, Scott Hamilton and B.A. Nicholson, [1] in their efforts to explain mid-19th century pit structures they discovered in the Lauder Sandhills, but for which there existed no clear explanation in the homestead era. Positing a continuous Metis occupation of the area from the early 19th century, Hamilton and Nicholson argue that the pit structures represent house structures, wells, and storage pits of rudimentary Metis farmsteads established after the post-1860 collapse of the Buffalo hunting economy in this region. While this paper does not take issue with most of Hamilton's and Nicholson's findings, it does present new evidence and challenge their interpretation of a continuous Metis occupation in the area. It argues instead that Metis occupation occurred in two quite distinct periods. One occupation, dating from the early 1840s through the 1850s, consisted of temporary wintering communities occupied by Metis buffalo hunters who participated in the burgeoning buffalo-robe trade. This occupation and settlement was entirely abandoned in the 1860s as the buffalo herds withdrew further west with the Metis following in their wake. The second occupation, dating from the late 1870s, involved more permanent agricultural settlement after the buffalo had disappeared from the Canadian plains. At this time those Metis who knew the Oak Lake area and its resources returned to establish homesteads.

This two-stage settlement process better explains the pit structures that Hamilton and Nicholson found, which should more accurately be attributed to the Metis wintering villages of the 1850s. In having ruled out this possibility, Hamilton and Nicholson have underestimated the size and complexity of some of these earlier settlements. This paper also posits, for the first time, that after the buffalo disappeared from the Canadian plains there was a significant number of Red River Metis who returned to Manitoba, albeit not necessarily to the river lots of the Red and Assiniboine rivers.

The first European occupation of the Souris River/Oak Lake Region occurred at least by the 1780s when the North West Company, numerous of its Canadian competitors, American traders, and later the Hudson's Bay Company traders began to establish posts on the Assiniboine and Souris Rivers. As the Assiniboine River constituted an important east-west transportation artery, and as large herds of buffalo wintered in the Turtle Mountains-Souris Basin region until the 1860s, these posts became not only fur-trading posts, but important provisioning posts collecting the dried buffalo meat and pemmican needed for the northern fur brigades. [2] After the merger of the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company in 1821, the Company closed Brandon House, its last remaining post in the area, in 1823-24. [3] The HBC met the American and free-trader competition in this region by outfitting Cuthbert Grant to trade for them. This was regularized in 1828 by the Council of the Northern Department when it appointed Grant as "Warden of the Plains" at £200 per year, with the explicit instructions that he prevent the illicit trade in furs in the Souris River Region. In order to expedite both his trading and "warden" activities, Cuthbert Grant built a post known as Fort Mr. Grant on the banks of the Souris near the present-day town of Hartney. [4] In 1828, he is reported to have brought out 50,000 Musquash (muskrat), as well as a quantity of provisions, buffalo robes, and leather. [5]

In the period after 1830, the only other post known to have operated in competition with Fort Mr. Grant was Fort Desjarlais, built in 1836 by Joseph Desjarlais. This second independent post operated until 1856 when it burned down. While of minor importance in the collection of furs, these posts were important for the trade in buffalo meat and robes. As long as the buffalo continued to winter in this region, these posts would continue to operate in winter, and given the significant number of Metis who wintered in this region (see next section), these posts would have had a significant fort population as certain times of the year. [6] John Palliser, travelling though this area in the fall of 1857, noted that Fort Mr. Grant was only a small winter post and was deserted at that time (see figure 1). [7] When the buffalo abandoned the Souris Plains for good in the 1860s this post would close for good as the Metis moved further west. [8]

Cuthbert Grant and his fur trading post were not the only links of the Souris River region to the Metis of the Red River Settlement, particularly those of the White Horse Plains or the Parish of St. François Xavier. When the organized buffalo hunt out of Red River began to replace more individualized hunting in the 1820s, the Metis of Red River used to rendezvous at Pembina to make a unified expedition or approach into Sioux Territory to the west where most of the buffalo herds were concentrated. [9] As the size of these hunts increased, parallelling the population increase of the Red River Settlement in the 1820s and 1830s, the single hunt split into two parties. There was the "main river party" encompassing the parishes along the Red River including Pembina, and a second "White Horse Plains Party," incorporating the Metis who had settled on the Assiniboine River at St. François Xavier and St. Charles. [10]

This second group or party increasingly took a separate route to the buffalo plains to the southwest. Instead of heading south to Pembina, the St. François Xavier Metis followed the Yellow Quill trail which skirted the Assiniboine River on its north side. They followed this trail through the Sand Hills to the mouth of the Souris, where they crossed the Assiniboine and headed south. [11] Here, on the Souris Plains where there was an abundance of grass, water, game, and the convenience of Grant's and Desjarlais' forts, they made plans for their summer buffalo hunt.

By the 1840s, some of these St. François Xavier Metis began spending their winters in the Souris/Oak Lake Region. During the late 1830s and early 1840s, the trade in buffalo robes began to replace the beaver trade on the Upper Missouri. These robes, consisting of the skin of the buffalo with the hair left on and the hide tanned, were best taken from November until February

when the winter hair of the buffalo was its thickest. Given that the buffalo no longer wintered close to the Red River Settlement by the 1840s, those Metis involved in the Buffalo Robe Trade had to winter on the plains at sites where the buffalo could be found. In the 1840s, prime wintering locations were found at places like Turtle Mountain, the Souris River Valley, Oak Lake, Whitewater Lake, and Pelican Lake. As late as 1857, Henry Youle Hind reported that the buffalo had been extremely numerous the whole of the winter on the Sand Hills and Valley of the Souris River. [12]

These hivernant or wintering villages became the home base for both buffalo hunters and traders. These wintering villages provided Metis traders with a secure base of operations to trade with the various bands of plains Indians in the region, and they provided the Metis buffalo hunters with a community and safety where they could live with their families who constituted the labour for the production of buffalo robes. The size of these communities could vary in size from a few families to large encampments with hundreds of inhabitants. In September of 1845, Father Belcourt, travelling with the Red River buffalo hunt to the Cheyenne River, noted a considerable group of Metis around the Souris River where they had established their hivernant camps. [13] Five years later, Belcourt again noted a concentration of Metis around the area of Turtle Mountain and on the Souris plain. They were in the process of gathering their winter provisions and erecting their winter shelters. He noted 30 houses at the foot of Turtle Mountain, 15-20 more families further up the Mountain, and as many as 400 Metis camped on or near the Souris River. They located here in winter because of the abundance of buffalo who also found winter shelter and pasturage in this locale. [14]

Metis winterers congregated in villages for both convenience and safety. These villages or encampments consisted of huts roughly constructed, but sufficient to protect them from the weather and to afford them room for goods and furs. They settled in sufficient numbers to protect themselves from hostile bands of Sioux, Assiniboine, and Blackfeet, and they chose sites with easy access to wood and water, and close to where the buffalo wintered. They built their cabins in late fall and abandoned them in spring when they returned to the Red River Settlement or American trading centres to trade their furs and robes. They would spend a month completing their business and then leave for the plains to take part in the summer buffalo hunt or return to their wintering quarters. Often they returned to the same site year after year when the buffalo remained in the area. This was the case with many hivernant sites at Wood Mountain, Cypress Hills, Buffalo Lake, and appears to have been the case in the Oak Lake area until the 1860s.

The temporary nature of these wintering sites and structures led Scott Hamilton and B.A. Nicholson to conclude that the substantial pit structures they had found must have dated to a later more permanent settlement period where year-round occupation was the norm. [15] This assumption, however, is erroneous in the sense that these communities could have been occupied year after year, and could have included substantial structures, especially those of the more prosperous Metis traders. Given that the pit structures that Hamilton and Nicholson found cannot be correlated to any settlement in the homestead era, and as almost all evidence points to abandonment of the Oak Lake/Souris Plains area between 1860 and 1880, these pits are most likely related to the buildings in a Metis hivernant village.

The basic social and material components of these hivernant villages was much the same across the western interior. Most consisted of Metis hunters and their families, a few Metis traders, and by the 1850s a mission priest at the larger sites. The houses that sheltered this population were rude one-room shanties built very quickly using only an axe and a crooked knife. These shanties were virtually identical to each other and consisted of one room. They were built of rough poplar or spruce logs morticed together at the corners of the building. The walls were approximately six feet high in front and a little over five feet behind. A large clay fireplace or chimney took up the space of one of the exterior walls. Doors and windows were simply cut out of the solid log walls, and a door could be built from the boards of a cart. Windows consisted of a piece of parchment, and the roof was covered with straight poles, over which was placed a thatch of marsh grass weighed down with loose earth. The lowness of the building was sometimes remedied by digging out the ground for two feet. [16] tuart Baldwin, "Wintering Villages of the Metis Hivernants" in Metis Association of Alberta (ed.), The Metis and The Land in Alberta Land Claims Research Project, 1979-80 (Edmonton: Metis Association of Alberta, 1980); D, Grainger and B. Ross, "Petite Ville Site Survey, Saskatchewan," Research Bulletin, No. 143 (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1989); H.M. Robinson, The Great Fur Land or Sketches of Life in the Hudson's Bay Territory (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1879); Mary Weekes, The Last Buffalo Hunter (New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1939); Isaac Cowie, Isaac Cowie, The Company of Adventurers: A Narrative of Seven Years in the Service of the Hudson's Bay Company During 1867-1874 (Toronto: William Briggs, 1913).

Wealthier traders living in these villages, however, would have multi-room dwellings with gabled roofs. These traders' dwellings were often the site of religious services and dances, and accommodated not only the traders' retinue of relatives and followers, but also his trade goods. They usually had a second dwelling to serve as a storehouse for gunpowder, furs, robes, leather, and provisions. [17] This is probably the type of structure, or the remains of which, that Hamilton and Nicholson found in the Lauder Sandhills. The following photograph of a more substantial wintering structure at Wood Mountain would seem to meet all the criteria or characteristics that Hamilton and Nicholson describe.

FIGURE 3

By the early 1860s, however, with the diminishing buffalo herds retreating further west, the Oak Lake area ceased to be a good wintering site. Metis hivernant sites moved further west to Wood Mountain, Cypress Hills, and the Milk River regions. Even Fort Mr. Grant was closed permanently in 1861. There would have been little reason for the Metis buffalo hunters or traders who had frequented the Oak Lake area to remain.

Even though there is no solid evidence of any other economic activity in this region, Hamilton and Nicholson argue that some Metis families remained on in the Lauder sand hills after the bison had left. [18] They speculate that they stayed because of the utility of subsistence farming, trapping, and hunting, [19] in part to provide the pretext for the pit structures they found. As I have already argued, these pit structures more likely date to the hivernant sites a decade earlier. The search for more concrete evidence about possible occupation in the 1860s has resulted only in evidence to the contrary. Of those Metis who were living in the Oak Lake/Grand Clairiere region in 1885-86, and who applied for scrip, none acknowledged living in the area prior to 1878. [20] Even Philomene Lafontaine, who was the primary Metis informant for local historians in the 1930s, noted that she had left the area in the 1860s and had not settled there permanently until 1880. [21]

FIGURE 4

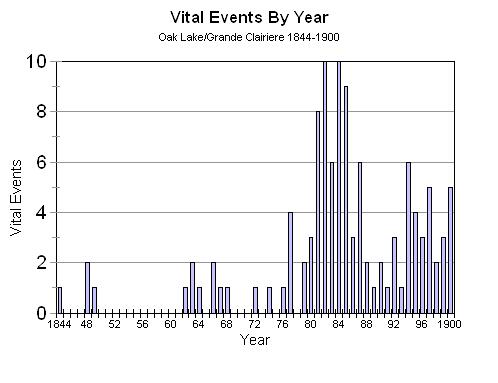

The examination of vital events (births and deaths) recorded in Metis scrip applications and parish registers [22] also suggest permanent occupation began only after 1877. Although there is evidence that a few births and deaths took place at Oak Lake between 1860 and 1876, a close examination of this handful of events shows that they were not related to any permanent occupation of the area. That is, those parents who noted in their scrip applications that one or more of their children had been born near Oak Lake in this period were all living somewhere else or were plains hunters of no fixed abode.

Of the eleven births listing Oak Lake as the birth place between 1860 and 1876, three were the children of Joseph Larocque and Madeleine Fagnant who noted in 1885 that they were living at Qu'Appelle, and that they had always resided on the plains and were plains hunters. Marie (born in 1862), Joseph Jr.(born in 1866), and Florestine (born in 1872) had been born at or near Oak Lake on the way to the Red River Settlement. [23] The other births occurring at Oak Lake in the 1860s and 1870s were likewise not connected to any settlement there. The two children of Antoine Fagnant and Marie Ledoux (Melanie born in 1863 and Charles born in 1867) note on their scrip applications that they were born at Oak Lake, but note that until 1869 their parents had resided permanently at St. François Xavier in the Red River Settlement, and that they had been born at Oak Lake returning from a hunting excursion. After 1869 they, along with their parents, had left the Red River Settlement to become plains hunters in the Qu'Appelle Valley where they had resided ever since. [24] The details of the other six births are almost identical in nature. [25] What these scrip applications make clear is that the births that occurred at Oak Lake in the 1860s and 1870s were of Metis living on the plains and only passing through the Oak Lake district. Given that Oak Lake was a known camping spot on the trail leading from the Qu'Appelle Valley and Fort Ellice to the Red River Settlement, and given it had abundant pasturage, water, and game, it would have been a good location to camp while women were in childbirth.

Permanent settlement at Oak Lake did not occur until the late 1870s when the last of the large buffalo herds disappeared from the Canadian Plains. Metis plains hunters and traders were now faced with a decision of whether to take treaty or settle down somewhere. From the evidence available, it is clear that a number of these plains Metis families chose to return to Manitoba and settle permanently at Oak Lake. They were families who knew the region from an earlier wintering occupation of the area.

The first permanent Metis settlement of the Oak Lake area in 1877-78 was by Red River Metis who had left the Red River Settlement during the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s, and who began to drift back to Manitoba in the post-buffalo era. According to one of the first settlers, Amable Marion, Metis began returning to Oak Lake around 1878 when the buffalo herds began disappearing from the Canadian plains. They were joined by other plains hunters from the west in the years 1879-81 and took up homesteads along the shores of Oak Lake and along the Assiniboine between the town of Oak Lake and Griswold (see figures 5 & 6). [26] Amable Marion was joined at Oak Lake by his brothers and sons (Maxime, Narcisse, Roger, Norman and Adolph), [27] and within a year or two they welcomed the families of the Lafontaines, Berards, and Brelands. Most of these Metis were either hunters or traders who now settled at Oak Lake to begin farming. The abundant waterfowl on Oak Lake provided extra food, and the close proximity to the Fort Ellice trail provided opportunities to make extra money in freighting.

Some insight into the life courses and movements of these Metis families can be gleaned from scrip applications taken between 1885 and 1901. Antoine Lafontaine noted in 1901:

I was married at St. Francois Xavier about thirty-nine years ago [1862]. I had been ‘tripping' in the west. . . . I lived in Manitoba in the winter and hunted in the summer. I settled permanently at Oak Lake about twenty years ago [1880-81] and have lived there ever since. . . I resided at Grande Clairiere and Oak Lake twenty-two years. Before that on the Prairies. I left St. Francois Xavier in 1870. . . . I moved to Cypress Hill around twenty-nine years ago (1872). I have always moved about the prairie. I moved to Hartney fifteen years ago [1885-86] and have lived there ever since. [28]

His wife Philomene Jannot noted in 1901 that she had lived in St. François Xavier with her parents until she married Antoine Lafontaine in 1862. Following her marriage, she noted, they immediately left for the west. The settled at Oak Lake in 1881. The birth and death places of her 13 children read like a travelogue of the Buffalo plains. [29] The trajectory of Calixte Lafontaine and his family, who settled at Oak Lake between 1877 and 1880, is somewhat different. Calixte, though a plains hunter, retained a residence in St. François Xavier until he sold his river lot in 1877. He then moved to the plains settling at Oak Lake with his large family shortly thereafter. They did not remain long, however, moving to Batoche between 1882 and 1884.

Those Metis who remained at Oak Lake began to break the land and farm, [30] and were soon joined by a few French-speaking settlers from Quebec and France. Crucial to the survival of this community, set in the middle of a sea of Anglo-Canadian settlement, were the services of the Catholic Church. Served initially by itinerant priests from Brandon, Willow Bunch, and St. Boniface, [31] the Metis and French of Oak Lake petitioned Archbishop Taché for a resident priest in 1886, noting that they had no one among them to baptise, marry, or bury them, and their children were unable to take catechism. This petition was signed by both French Metis and Quebec and Belgian French and gives some idea of the families in the community in 1886. [32]

| Figure 7 – Petition for Resident Priest 1886 |

||

| METIS |

NON-METIS |

|

| Andre Berard |

Thomas Breland |

Francois Deleuque |

| Wm. Dauphinais |

Casimir Dauphinais |

Joseph Lapierre |

| Joseph Courchene |

Ernest Ducharme |

Auguste Blondeau |

| J. Baptiste Davis |

Francois Gervais |

Aime Marcotte |

| Maxime Marion Jr. |

Amable Marion |

Theophile Poirier |

| Maxime Marion Sr. |

Antoine Gladu |

Janvier Loiselle |

| Napoleon Lafontaine |

Antoine Lafontaine |

Joseph Turcotte |

| John Leveiller |

Joseph Leblanc |

Hormislas Fileau |

| Maxime Rielle |

Wm. Lafournaise |

Antoine Eneault |

| James Whitford Jr. |

James Whitford Sr. |

Joseph Carpentier |

Taché finally dispatched Joseph A. Bernier, a Quebecois Priest, in 1887. He quickly began to build a church in the railway town of Oak Lake, but lived among his Metis parishioners close to the lake itself (see figure 6).

This new parish was crucial to the viability of the Metis community. Though most accounts of the Oak Lake Metis stress the dissolution of the community as Anglo-Canadian settlement became dominant in the area, the evidence suggests otherwise. As long as Father Bernier worked among his Metis parishioners the community persisted and the church expanded. As late as 1891 Le Manitoba reported that a bazaar had been held in the town of Oak Lake to raise money for the Saint Athanasius Church and that the bazaar had successfully raised $841.27. This success, the correspondent noted, illustrated the perfect harmony among the various nationalities in the area. [33] In 1892 the town formed a local of the St. Jean Baptiste Society, [34] and the church was being expanded. [35] In 1893 the chapel of the church was being refurbished, a presbytery was being built, and plans had been made to construct a French school in the town of Oak Lake. [36] It was the sudden death of Father Bernier in late 1893 at the age of 36 that stopped all of this. No replacement for Bernier was sent until 1902 and the French Metis community melted away. The reason no replacement was sent for close to ten years was probably related to the fact that a second Catholic parish had been established in 1888 at Grande Clairiere 18 miles to the south (see figure 5). Although Grande Clairiere might well have supplied the necessary religious services for individual Metis, the absence of a parish priest at Oak Lake had disastrous consequences for the Metis community there. One by one the Metis sold out, either to move closer to the Catholic church at Grande Clairiere, to other Metis communities at Belcourt and Dunseith in North Dakota, or to move further west to homestead in Saskatchewan.

The story of Ambroise Lepine [37] illustrates the dilemma and demise of the Oak Lake Metis community. Lepine had moved to the growing community of Oak Lake in 1891 after his house in Grande Pointe, just south of St. Boniface, burnt to the ground. He moved to Oak Lake, he said, because his brother-in-law Roger Marion was already established there on a large farm. Lepine bought a farm nearby (see figure 6) and began farming. Bad harvests and other failures left him nearly penniless, but it was the refusal of the Archdiocese of St. Boniface to send a replacement priest for Father Bernier that left him bitter. By 1898 he was complaining to Mgr. Grandin that he was surrounded by English Protestants. The other Metis had sold and moved out after the death of Bernier when the Church had not sent a replacement. [38] Lepine lasted a few more years, but in 1907 he pulled up stakes and moved to Forget, Saskatchewan where two of his sons were already homesteading.

The Metis community of Oak Lake, however, had not failed for lack of French-speaking neighbours. The near-by community of Grande Clairiere, composed largely of French-speaking settlers from France, Belgium, and Switzerland, must also be taken into account to understand how the Metis identity of this region disappeared. Grande Clairiere was founded in 1888 after Father Jean Gaire arrived in Manitoba from France. Dispatched to the Oak Lake Mission he found Joseph Bernier had already established a church there and determined to locate a second parish south of Oak Lake. Travelling approximately 18 miles south, Gaire arrived at a small settlement of Metis near Maple Lake that included the farms of Jean Leveille and Thomas Breland. Here he took out a homestead (SW30-6-24W) and began building a small house. [39] Although Gaire always had good relations with the eight Metis families who lived nearby, his real interest was the colonization and settlement of the area with settlers from France and Belgium. During his first few years in Canada, Gaire returned to Europe a number of times to bring back hundreds of colonists to Grande Clairiere. [40] This colonization scheme had the effect of slowly but surely obliterating the Metis identity of the Oak Lake/Grande Clairiere area and replacing it with a French or Franco-Manitoban identity.

Gaire's new parish and colonists had undercut the Metis parish of Oak Lake almost from the first. As early as 1890, Gaire was petitioning Archbishop Taché to detach township 7 from the Oak Lake parish and attach to his own at Grande Clairiere. The ostensible reason was that Grande Clairiere was closer and that during wet weather the Plum Lake marsh made travel by horse difficult (see figure 8). [41] This competition for parishioners undoubtedly hurt the more Metis Oak

Lake parish, and following Father Bernier's death in 1893, the French, as opposed to Metis, identity predominated in the Oak Lake/Grande Clairiere area.

This paper has argued that although the Oak Lake/Souris Valley region had long been occupied and exploited by the Plains Metis, this occupation occurred in a two-stage process. Permanent settlement only occurred in the period after 1878 when the buffalo disappeared from the Canadian plains, and a significant number of Red River Metis returned to Manitoba. Their identity as Metis communities, however, was not only challenged by the surrounding Anglo-Canadian settlers, but also by the large number of French-speaking Catholic settlers from Quebec, France, and Belgium. Although these groups lived in general harmony, the greater danger came from the French Catholic community of Grande Clairiere whose priest, Father Jean Gaire, was preoccupied in colonizing the area with French-speaking European settlers. The Metis of Oak Lake, dependent on Father Joseph Bernier and the St. Athanasius for the institutional base of their ethnicity and identity, had few places to turn when Bernier died in 1893 and he was not replaced. Some Metis moved south to Dunseith and Belcourt to join the Turtle Mountain Metis community, some relocated to Saskatchewan to start over, and still others joined the Grande Clairiere community. This last option, however, placed them in a community that was French or Franco-Manitoban – not Metis.

[1] Scott Hamilton and B.A. Nicholson, "Métis Land Use of the Lauder Sandhills of Southwestern Manitoba," Prairie Forum 25, no. 2 (Fall 2000).

[2] For an inventory and brief history of these posts see: David A. Stewart, "Early Assiniboine Trading Posts of the Souris-mouth Group 1785-1832," Transactions of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba, No. 5, New Series (July 1930); G.A. McMorran, "Souris River Posts and David Thompson's Diary of His Historical Trip Across the Souris Plains to the Mandan Villages in the Winter of 1797-98," (Souris: Souris Plain Dealer, n.d.); G. A. McMorran, "Souris River Forts in the Hartney District," Transactions of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba, Third Series (1948-49).

[3] G.A. McMorran, "Souris River Posts and David Thompson's Diary," 13. The Hudson's Bay Company briefly reopened Brandon House between 1829-32. See Ibid., 15.

[4] Margaret MacLeod and W.L. Morton, Cuthbert Grant of Grantown (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, Carleton Library, 1974), 99-101. This post has been located on Sec. 7, Twp. 6, R. 23.

[5] Ibid., 100.

[6] G.A. McMorran, quoting an interview with a Mrs. Lafontaine who had spent her childhood winters at Fort Desjarlais, notes that there were always between 75-80 men at Fort Desjarlais. G.A. McMorran, "Souris River Posts and David Thompson's Diary," 13. This seems unlikely given the relative importance of these posts, but as this area was a prime Metis wintering site in the 1840s and 1850s, it is not impossible that the Metis would have congregated around these posts at various times of the year.

[7] Irene Spry (ed.), The Papers of the Palliser Expedition 1857-1860 (Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1968), 119.

[8] Fort Mr. Grant was closed for the last time by Thomas Breland, Cuthbert Grant's grandson, in 1861.

[9] Gerhard J. Ens, Homeland to Hinterland: The Changing Worlds of the Red River Metis in the nineteenth century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 38-43.

[10] W.L. Morton, "Introduction," to London Correspondence Inward From Ede Colville 1849-52 (London: Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1956), xxxvi.

[11] Ibid., xxxvii. Travelling through the same area in 1857, Henry Youle Hind noted that the buffalo hunters' trail crossed the Assiniboine going south at the Souris River. Henry Youle Hind, Reports of Progress Together with a Preliminary and General Report on the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition (Toronto: John Lovell, 1859), 30.

[12] Ibid., 48.

[13] Letter of G.A. Belcourt, St. Paul, November 25, 1845. Printed in House of Representatives Executive Document, No. 51, 31st Congress, 1st Session, 44.

[14] G.A. Belcourt to Bishop of Dubuque, 16 Fev. 1850. Ann. de la Prop. de la Foi, 106-110.

[15] Scott Hamilton and B.A. Nicholson, "Métis Land Use of the Lauder Sandhills of Southwestern Manitoba," Prairie Forum 25, no. 2 (Fall 2000), 257.

[16] For more detail on Metis wintering sites and the structures in these villages see: Jack Elliot, "Hivernant Archaeology in the Cypress Hills," MA Thesis, University of Calgary, 1971);

[17] Isaac Cowie, The Company of Adventurers, 349-350.

[18] The only evidence Hamilton and Nicholson point to for continued occupation of the Lauder Sand Hills is a brief reference in the local history of the Souris Valley that notes an unknown number of Metis in the area. See Lawrence B. Clarke, Souris Valley Plains: A History (Souris: Souris Plaindealer, 1976), 105. Hamilton and Nicholson also speculate that a vague reference to a ranch in the sandhills in 1875 might have been that of James Whitford. Scott Hamilton and B.A. Nicholson, "Métis Land Use of the Lauder Sandhills," 263. This cannot be the case. In the scrip application of Joseph Whitford (James Whitford's son), Amable Marion swore and affidavit that James Whitford only settled in the Oak Lake Area in 1879 and only moved to the Sandhills in the mid 1880s. RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1371.

[19] Scott Hamilton and B.A. Nicholson, "Métis Land Use of the Lauder Sandhills," 251.

[20] In applying for scrip, each Metis applicant had to provide a life history indicating where they were born, where they had lived and when, when they married, and what the names of their children were, and when and where they had been born.

[21] Philomene Lafontaine was interviewed in 1934 about the previous history of the area. See G.A. McMorran, "Souris River Posts and David Thompson's Diary," 56.

[22] Parish registers for Oak Lake and Grande Clariere only begin in 1887-88.

[23] See scrip applications in National Archives of Canada (NA), RG 15, D-II-8-b, Vol. 1329; and D-II-8-c, Vol 1354.

[24] See scrip applications in NA, RG 15, D-II-8-b, vol. 1327.

[25] Theophile Fagnant, listed as born at Oak Lake in 1863, noted that he had lived on the plains near Regina all of his life until he moved to Qu'Appelle in 1888, (RG 15, D-II-b, Vol. 1327). Elise Cayen, born in 1864 near Oak Lake, noted that she had lived on the plains all her life and her parents were only temporarily wintering at Oak Lake when she was born (RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1340). The heirs of Helen Lavallee noted that she had been born at Oak Lake in 1868 and had lived her whole life in the Qu'Appelle district, dying there in 1884 (RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1355). The application of Michel Houle, who was born east of Oak Lake in 1874, noted that the had been born on the way to Winnipeg from Wood Mountain (RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1351). Eliza (1866) and William Ross (1876) both of whom list Oak Lake as their birth place also noted that they lived with on the plains at Qu'Appelle (RG 15, D-II-8-b, Vol. 1331).

[26] Affidavit of Amable Marion in support of scrip application of Antoine Lafontaine. NA, RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1353).

[27] The Marions were originally from St. François Xavier and St. Norbert in the Red River Settlement, and had hunted and traded between Wood Mountain and Cypress Hills in the early 1870s prior to moving to Oak Lake. See Scrip application of Maxime Marion for his deceased daughter Adele in 1901. NA, RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1357.

[28] Various affidavits of Antoine Lafontaine to support the scrip applications of his deceased children in 1900-01. NA, RG 15, D-II-8-c, Vol. 1353.

[29] Ibid., Affidavits of Philomene Lafontaine for the scrip applications of her deceased children.

[30] Notices from the French Metis settlement at Oak Lake began appearing in Le Manitoba after a permanent Catholic Mission was established there in 1887, and these notices emphasized the grain crops being harvested.

[31] By 1884 Father Decorby had established a temporary mission station at Oak Lake but was there only briefly each year. Archives of the Société historique de Saint-Boniface, Fonds Archevêché de Saint-Boniface, Decorby to Taché, 7 juin 1884, T29530-32.

[32] Archives of the Société historique de Saint-Boniface, Fonds Archevêché de Saint-Boniface, Petition pour avoir un prêtre au Lac des Chênes, 8 oct 1886.

[33] Le Manitoba, 15 avril 1891, p. 3.

[34] Ibid., 20 avril 1892, p. 3.

[35] Ibid., 13 juli 1892, p. 3.

[36] Ibid., 20 septembre, 4 octobre 1893.

[37] Ambroise Lepine was born in 1840 and hr married Cecile Marion in 1859. He was appointed Adjutant-General of Louis Riel's Provisional Government in 1869, and as such headed the Metis Court Martial that condemned Thomas Scott to death in 1870. Unlike Riel, he refused to stay in exile and when he returned to Manitoba in 1873, he was arrested and tried for the murder of Scott. Though sentenced to death in 1875, this sentence was commuted to two years in prision, and he was released in 1876. He lived in St. Boniface until 1880 when he moved to Grande Pointe.

[38] Archives of the Société historique de Saint-Boniface, Fonds Archevêché de Saint-Boniface, Ambroise Lepine to Mgr. Grandin, 7 janvier 1897, L10878-81

[39] Jean Gaire, Dix Années de Mission au Grand Nord-Ouest Canadien (Lille: Imprimerie De L'Orphelinat de Don Bosco, 1898), 27-40.

[40] Ibid. See also J.G., "Grande Clairiere, Manitoba," Le Manitoba, 10 dec 1891.

[41] Archives of the Société historique de Saint-Boniface, Fonds Archevêché de Saint-Boniface, Gaire to Taché, 29 avril 1890, T42751-42753; Gaire to Taché, 8 juli 1890, T42814-42817.