Ever-increasing energy consumption and its consequential production increases has been the reality of our lifetime. In fact, it has been the reality since the inception of the Industrial Revolution these past 200 years or so.

No energy mode or system that has ever been commercialized is without environmental impact or consequence. There is nothing new about this fact. Indeed, one can find evidence of this interaction going back into the earliest days of antiquity. Eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamian sites dating back to the pre-iron age of Bronze provide ample evidence of localized overuse of resources, of misuse to the point of abuse and local/regional depletion. After only a few decades, in most cases, the relentless pressure of demand for timber for charcoalization with which to smelt copper into bronze proved to be the undoing of one centre of civilization after another. Resources were eventually depleted; the landscape denuded, the environment scarred and/or made more vulnerable to erosion by wind or run-off. What has changed is the scale of it all.

What helped to ensure that this phenomenon did not then become vast in scale was a combination of three factors. The human population was always very much smaller than during our time. Furthermore, the proportion of that ever so much smaller world population engaged in resource extraction and smelting (as opposed to primitive hunting and gathering) was, in turn, very limited. Then too, when overshoot did occur in those limited number of places; the crash was followed by only local depopulation. The "activity of civilization" either moved short distances to a new and pristine geography or else succumbed to a return of a dark age, or as some might wish to argue — a return to a more blissful state of nature — à la Rousseau presumably.

One can trace this same rise and fall of civilizations cycling with resource availability (and then eventual overuse) throughout history. After the transition from the ancient Bronze Age to the Iron Age and the decline of Greco-Roman civilization, came the medieval economy of primitive local dependency and self-reliance. Whether life was idyllic or nasty, brutish, short depends presumably on the reader's preinclination, and on one's degree of acceptance of the premises put forward by Jean Jacques Rousseau at one extreme or Thomas Hobbes at the other.

Still, the world evolved even if it appeared to be in steady state. For a thousand years or more, the population was kept in check by natural attrition. Yet, despite a very slow evolution of methods of production by the late Middle Ages blending into early modern times in Europe especially (circa 1500), there was a return of patterns of excessive resource use (and environmental disaster). In England and on the continent, the 1500s and 1600s were a time of denuding of forests and majestic old growth to feed the charcoal smelters of iron based metallurgy. Nothing could stop the process until entire forests disappeared. There was obviously little thought and certainly no action then to practice silviculture and reforestation. This could be said of Canada and the US even 400 years later — until about 1970.

There can be little doubt that controversy surrounded this denuding of the forested countryside but what was the alternative? It arrived technologically by way of the coking of coal. The problem of sulfur impurities in most coal which caused embrittlement of iron thus smelted, and therefore and inferior product, was now solved. This innovation in the use of coal quickly gave some relief to a Europe growing increasingly alarmed at the rate of deforestation, due in large part to metallurgical demand and to the heating and cooking needs of the general population.

This development in the 1700s should be viewed in the total context of the Age of Discovery, by then in its second century of continued exploration, trade and settlement overseas in the Americas and parts of Asia and Africa. In the two centuries, i.e., 1712 to 1912, we can see fundamental developments that alter the human condition in a remarkable way. Each of these developments eased the pressure on forestry and on the soil resource, already over cropped and tired, of Europe.

I have already referred to Lord Darby's discovery of the ways to use coal in the making of iron and steel without downgrading quality. Soon after, with the complimentary invention of the steam engine and of coal-based steam engine energy came another major change to industrial modalities. In addition, with that came the eventual replacement of rural life and of an overwhelming rural population by increasing an urbanization. This is a process that has continued on all continents for the last 200 years, impacting on Latin America and Africa more slowly and more recently. Still it continues to this day. The politics of demographic change (which is a vast study of its own) derives nonetheless, from the coming-together of events surrounding coal, steam and engines and one other, which came at the end of this 200-year period.

In 1910-1913, industrial chemistry, largely through the efforts of Fritz Haber, succeeded in finding a technological solution to the problem of declining soil fertility and nitrogen levels in tired over-exploited soils. The Haber process for fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere and combining it with hydrogen to form ammonia was, and remains, a dramatically successful synthetic alternative to Chilean saltpeter and bird guano. All at once the concerns that one or another military power might attempt to monopolize or blockade these life-sustaining sources of fertilizer, and therefore of food, became almost irrelevant. The desperate search for new and fertile food producing lands that drove the "colonial mentality" could now be ended and replaced by more justifiable foreign policies.

Ironically, it is because the British strategists, in 1914, did not know of Germany's industrial capacity to synthesize ammonia, that they believed that a sea blockade off the coast of Chile/Peru would deny Germany access to both fertilizer and nitrates for explosives and would force their capitulation after a very "short war". The German side, thinking that their surprise technology gave them superiority in food production and explosives manufacturing, gambled on a quick and surprising victory. The politics of resource exploitation and technological substitution had reached new heights of reckless speculative strategizing.

There is still one other transcending consequence of resource use and depletion in Europe that must be mentioned in any treatise of resource use/misuse and politics. It is that as European renewable resources were consumed—sometimes beyond annual replacement or sustainable yield, and as nonrenewables were depleted—the pressure grew to deal with the problem of dwindling resource supply by taking advantage of European superior seafaring, navigation and weaponry to gain a foothold in landmasses across the Seven Seas. In other words, colonialism became the "conventional wisdom" and justification.

The fact that soil fertility losses and declining crop yields were not yet well understood until the late 1850s gave yet another motive to foster and encourage the increasing mood of imperial expansion and colonialism. The politics of 18th and 19th Century imperialism and the military props for colonial rule derive from the perceptions of those centuries regarding resource availability and the assumed need for new and fertile lands to feed a population now starting to grow rather more quickly and approaching one billion by about 1830. The colonization of the Western Hemisphere and Australia/New Zealand began in earnest.

Now let us turn to the mindset of those choosing to immigrate into the interior of vast continents of colonial empire. It is not hard to imagine or describe. Visualize, teeming wildlife, seemingly endless forests and vast distances and spaces. Not only was there no apparent reason to conserve and husband resources; the sheer magnitude of the task of clearing the land to make it suitable for crops and domesticated animals, created a psychology of "conquest of nature" rather than a stewardship for the "conservation of nature and nature's resources". Millions of trees were slashed and burned rather than being put to any use; millions of bison were slaughtered for no purpose other than "clearing the way" for settlement.

Lest we become too critical and indignant of this episode in history, we must simply empathize with those who viewed the world as so vast as to be virtually without end or limit in its ability to produce bounty without any resulting complications or cause natural catastrophe for humanity. Magellan and his crew barely survived three years of hardship on "never-ending" oceans, and others who were at all inquisitive of the world around them can hardly be faulted for regarding the earth to be virtually without end or limit when compared with man's puny capacity all those centuries to make any impact or difference. Given the technology of those years and a human population less than one-fifth of what it is today it is understandable.

Let us fast forward now to the modern era—the early 20th Century will do. Indeed, 1910 will do fine. That is the time, you will recall, that technological and scientific development brings to us the know-how and capacity for artificial fertilizer and thus enhanced food production. It was just about then, as well, that other historic events and combined chain of events were taking hold, and setting the stage for a sustained period of social, political and economic change.

Enter the internal combustion engine. (These changes were the result of the impact of cars, trucks, tractors and the oil that made it possible. At first all this was confined to both sides of the North Atlantic for the first 40 to 50 years). Since 1950 or so, it has increasingly become global in its economic and political effects. Nevertheless, it is continuing now into a full and complete century of rapid change. This has been characterized by approximately one hundred years (more or less) of telecommunication, of mechanical transportation, with its ever-increasing speed and mobility. The consumption of food and fibre, and increasing sizes of house and cottages have been relentless as well.

These increases have at times been on a per capita basis; in other respects on an absolute basis. As global population has increased from less than one billion throughout all the countless centuries before 1830, to about 2 billion by about 1930, then 4 billion by 1975, 5 billion by 1990

denigrated and 6 billion by 2000, one can sense we are entering a time in history when differences from the past are not differences merely of degree but rather differences in kind. This is all the more so because as humanity enters into this last century of six-fold increase, their appetite for per capita consumption increases as well. A double whammy!

After the decade of the 1930s Depression and World War II had become history; five

decades of rising expectations, demand and consumerism took command. The result was, at first, not negative. Great progress was being made in providing food, clothing, shelter and basic medical care for hundreds of millions of people. In a sense, there was improvement over a period of 40 years in living conditions for many people on most continents; but by no means was it universal. Then regression and back-slippage set in approximately by the late 1980s. The four-decade drive for greater equality in the human condition stalled out by 1990 or so and then, started to reverse as greater inequality in wealth and living conditions begin to reoccur by the very end of the 20th Century after 40 years of progress. However, this is outside the scope of this paper.

What becomes increasingly obvious in the post World Ware II era is that a growing population with growing aspirations and appetites and with rapidly deployable technology, equipment and manpower to harvest and/or extract and process earth's resources will be capable of extracting tremendous volumes of earth's resources and bounty. As long as all this can be done without exceeding annual sustainable yield (or renewable and sustainable harvest) these can be no real basis for raising any alarm.

But what if, demonstrably, this is not the case? What if the rate of extraction is far beyond sustainable yields? What if the rate of depletion of any given number of nonrewable resources has been manipulated onto a fast track that is ever escalating toward a date that is coming closer as all proven reserves are being exhausted or found to be exaggerated, either as to quality or cost of access and extractability?

Such a scenario calls for a sober reassessment of policy and practice and presumably a dedication to new directions in policy, i.e., in the politics and priorities we wish to endorse and embrace. Yet, this is not happening. Nor will it happen easily in the future. The reasons are as complex as are the current politics of energy and environmental protection; both at home and abroad.

There have been other occasions in the past when alarms were raised about the prospect of the "running out" of oil. The oil crisis of 1973-74 and 1979-80 come to mind. Both incidents were, however, the result of political embargoes and related geopolitical actions. In any case, these two events of 25-30 years ago recall to mind two other distinguishing factors. One was that it was in 1971 (but verifiable only in retrospect in 1973) it so happened that the US, by far the largest consumer of crude oil (and gas) and until then, also the largest producer was coming to a plateau and/or peak in its capacity to produce oil. This confirmation of future dependency on imported oil was bound to have some real effect; both in real and psychological terms.

The Middle Eastern members of the Oil Producers and Exporters Cartel (OPEC) used that psychological moment as the opportunity to embargo sales to western industrial importers in retaliation for their political support for the State of Israel. Non-Arab members of OPEC joined in the effort for economic reasons and managed to raise the price from $2 per barrel in 1972 to $12 per barrel by 1974. Do these numbers surprise? But, price was not the only thing to be changed then. That year was also the time when the major global oil corporations (then known as the Seven Sisters of World Oil) lost their complete control of oil production simply because the major producing countries moved in a determined way to take over the ownership and control of the oil fields and facilities in their sovereign domain.

Six years later, in 1979/80, the second OPEC crisis seemed a repeat but there were differences. Prices were hiked much higher, reaching $40 per barrel but only for a short duration—a spike. This, however, would have been equal to about $60-70 today. One other major difference from 1973/74 was that by 1980 the major oil companies were able to bring on-stream two major new discovery regions; the North Sea and the Alaskan North Slope. There had been enough time and all necessary investments to capitalize on the happy geological coincidence of oil-bearing strata in British and Norwegian North Sea waters and in Alaska. All of this came together to result in new oil production of about 6 million barrels per day. This was a 10% increment in global production, then running at about 60 million barrels per day. This was enough to bring prices down and reduce OPEC influence for the next ten years. Ironically, the desire for reverting to much lower prices was not shared by all western and industrial states because the multibillion-dollar investments in deep-sea production platforms and in Arctic pipelines now "needed" somewhat higher prices to provide amortization plus a reasonable profit.

The political complexity of opposing interests has many dimensions. If high oil prices had the effect of breeding the conditions for recession and stagflation, the return of low prices had the effect of discouraging research, development and investment in renewable energy.

It also had the effect of discouraging any efforts to persist with better standards of fuel economy and efficiency, with efforts to reduce car size and encourage energy conservation generally.

Thus, the politics of energy policy formation these past 20 to 25 years has been to downplay the concerns about eventual oil shortage and the price gouging that might ensue; at least until a year or two ago. An example of most dramatic and drastic change in energy policy and politics came in the US in the switchover from the Carter to the Reagan administration. President Carter's exhortation to reduce car engine sizes, turn down thermostats and to embrace the conservation ethic generally, was abruptly ended in 1981.

The Reagan era began with a speech encouraging Americans to welcome a "new morning" with no need to restrain resource use appetites any longer, including energy resources in particular. Support and encouragement for renewable R&D was phased out quickly.

So too, was encouragement for greater fuel efficiency and President Gerald Ford's lower speed limit campaign. This policy reversal coincided with new oil from Alaska's North Slope and the Britain/Norway North Sea. Prime Minister Thatcher's policy priorities seemed to encourage the fastest possible extraction and depletion of the newly found oil and gas reserves. Only Norway held out for a policy of retaining majority public ownership of production and for a more prolonged time frame for production at a somewhat slower rate. The result may have been a 20year bonanza for Britain—but as of 2002 (rather incredibly) Britain lives with a past-the-peak of oil production reality. Oil (and gas) production is now into the 4th year of a definitive decline. The country faces the certain prospect of becoming a major net importer of oil and gas within this very decade. The Norwegian example is quite different. In a way, the two scenarios are descriptive of the world's dilemna and choices in microcosm.

To be a responsible citizen in a world where nonrenewable fossil fuels are put to ever increasing and "ever faster track" depletion requires that ultimately citizens band together to demand reanalysis and redirection. We used to say that good citizenship requires literacy and that democracy requires a literate population. That remains true but it becomes obvious that to understand energy and environmental sustainability in this Modern Era now also requires a pervasive numeracy.

Historically there has been widespread unawareness and nonchalance about the depletion of oil and gas and the environmental unsustainability caused by the polluting and climate altering effects of the petroleum and petrochemical era.

For the first half of this era to about 1950/60, the full implications were seen only dimly. This was because the science of detection was just developing and because the scale of consumption and pollution was much, much smaller even 50 years ago. Identification of the problem was only timid and tentative before the 1960s. The really noticeable whistle blowing did start and in a two-pronged way in that decade. In respect of the growing and devastating pollution of the environment, Rachel Carson's publication in the US in 1962 of "Silent Spring" came as a thunderbolt. There were those who tried to suppress and/or denigrate its message but it could not be buried. It did have the effect of making it easier for those attempting to get at least some local cleanup of air, and water as well as improvements in esthetic and cosmetic appearances.

Soon after a group with an international horizon (albeit predominantly European) tried to arouse public attention to global limits to resources and resource extraction. This effort by the "Club of Rome" was, in a few years, dismissed as heresy and unsupportable. It will, I think, reappear with increased plausibility before long.

Later that same decade a group of geologists attempted to explain and expose the conundrum of the ever-increasing over-dependency on a significantly depleting energy resource—oil in particular. In every way that matters, the issue and phenomenon of unsustainable environmental impact is tightly linked to the unsustainable rates of resource consumption, "the using up", of oil and gas, as well as coal. Logical analysis should lead one to conclude that we have an indivisible interest to solve both these drastic problems; that of environmental collapse brought about by overloading of ecosystems and climate change, and as well, the collapse of industrial economics and civilization because of complete energy supply failure and quickly thereafter, the inability to provide the food and fibres in the amounts needed for a planet of 6 billion people. Both prospects are equally outré.

The politics of energy production, the politics of supply prospects and the politics of environmental protection seem to serve (or fail to serve) entirely different interest groups. Yet, the challenge is largely all of one piece.

To be sure, if there were truly widespread acceptance of the contention that fossil fuel combustion with its resultant 25 billion tonnes of annual CO2 were the principal cause of global climate change and that such change was upon us, then some action would become a moral imperative in the public forum. Slowly that consensus appears to be evolving but until the politicians see a clear public trend, most will not have the stomach for earlier action. It may then become action-just-in-time (if we are lucky). There is a great deal of evidence and logic to suggest that Planet Earth's oceans and forests, are vast enough to act as an absolute sink for great tonnages of CO2 as they have in the past. Planet Earth's resources and resiliency factors are indeed—vast. But they are not infinite.

The rational politics of all this suggests that there is a prudent and practical course of action. It is to adopt the precautionary principle that in the face of growing evidence, but lacking absolute certainty, the most justifiable course is to conserve and attenuate the use of nonrenewables while working hard to develop the renewables. It becomes essential to slow the rate of depletion of fossil fuels and hasten the rate of harnessing the renewables, i.e., wind and hydro.

Only those who have the most unlimited greed for profit by fast track depletion should have cause to object. No one realistically wishes for a disruption in the stability of the oil and gas industry, but their product would serve better if it were extracted at half the present pace rate and therefore remain available for twice as long into the future. On that basis, Earth's natural CO2 sinks would then have a somewhat better chance in the odds of absorbing the tonnages of CO2 that would still be emitted, but at greatly reduced levels each year.

However, as matters now stand, and with the prevailing attitudes, there isn't a chance that we will come through this without major disruption and consequential misery. I also hold this view as regards the political and technological problem of getting alternative energy systems in place before supply shortfalls in oil and gas drive prices even further into erratic haywire extremes. The 2004/05 price examples are merely the leading edge. In other words, we are leaving the task of redirecting our energy future dreadfully late—dangerously late. I mean this from the point of view of supply shortages that both explode price and disrupt production capacity of food, fibre and finished goods. By then, we may or may not yet, have the ultimate proof of impending climate change bringing environmental and ecological disaster. If these two prospects are linked, however, does it really matter which comes first?

Ironically, the linkage of these two transcending problems extends to the political world. There is infighting, even among groups who are genuine supporters of conservation policies. There are some who are environmental activists, because of visible impacts on the landscape and others who urgently support renewable energy initiatives because of sustainability concerns. Each of these groups have, within them, numbers who are impatient; who seek urgent measures in support of one or another policy initiative sometimes to the exclusion of all other options. In this context, one can meet those who favour the solar option and downplay wind energy and/or those who favour wind energy options as capable of meeting future energy needs without any need for development of hydroelectric sites, even of the most favorable kind. All this is rather remindful of the old adage—"every duck praises its own slough".

The reality is that the very scale and nature of the problem is so great that it requires the adoption of all practical efforts and renewable, sustainable alternatives. This includes promotion of the conservation ethic—use less, waste less. It includes promotion of all efforts toward greater efficiency in energy and resource use; building better, smaller and with more insulation, more allowance for solar gain, etc. These are some examples that come mind. Acceptance of new technologies that have passed tests of feasibility must be encouraged. The slow rate at which geothermal heat pumps are being installed as an alternative to gas heating is a disappointing case in point. The technology is known. The capacity to install must be encouraged and ramped up but who will do this? One potential stakeholder awaits the other and governments remain passive bystanders. So it proceeds at a snail's pace.

We perceive the political problem of breaking out of inertia. We appear, these past 20 years, to be living in a time when the dominant political philosophy guiding democratic governments is one of subordination to market forces. The path followed appears to be the opposite to that followed, e.g., by President Franklin Roosevelt in formulating the New Deal as a major struggle to reduce the poverty and despair of the 1930s. It was not left to chance then. Government was used as a useful tool—as an instrument to initiate certain programs and actions to seek certain objectives. At present, however, we drift without any guiding path or principles. The Kyoto Accord to reduce CO2 emissions has, for political reasons, been signed by most countries but not by others, including the US. It is important to note that there is, in fact, very little difference in the actual deeds thus far in either set of countries (except for a few in Europe). The quantum of fossil fuel depleted each year, and the resulting CO2 emissions keep moving in the direction opposite to the Accord. If this is progress, we must be using an inverted mirror.

There has been no shortage of government press releases (implying action and progress) issued since the Kyoto Accord was negotiated eight years ago, but precious little has been done. As such, all these press communiques have been used rather like Weapons of Mass Deception. Only Alice in Wonderland, who learned how to use the Mock Turtle's calculator can explain how we manage to imply we have made progress when, in fact, oil and gas depletion has accelerated in Canada as much as anywhere else and so have greenhouse gas emissions.

The political climate needed for any real and concerted action is apparently not yet at hand. Wildly contradictory statements by opposing camps of experts confuse and perplex those citizens who try to make sense of it all. But wait! The most recent events of the autumn of 2005 are beginning to show an unintended consensus, but a consensus nonetheless. We have, in recent years, begun to hear more and more from those who describe oil depletion as a global problem; global in scope and disastrous in its consequence, if not urgently addressed. These "peak oil" geologists (and others of the same view) were, until about 1995, few in number and viewed with derision by the conventional wisdom, and of course, by those hyping stock market shares and grinding other axes of self-interest. But these past two years they have been and are receiving respectful attention and are being joined in their efforts to explain, inform and educate, by some numbers at least, of economists, bankers and public policy analysts. They are no longer dismissed as doomsayers except perhaps by those who engage in the conventional wishful thinking that oil and gas will be available forever.

In early November 2005 the International Energy Agency, which is the agency owned by the 22 or so major oil consuming industrial nations, released an astonishing statement indicating that the world's energy consumption patterns and practices were unsustainable and urged major changes. One must pause here to have that resonate and register. Particularly so, because the IEA has, until now, always tried to put an optimistic face on global energy future prospects. One can be sure that there has been, these past six years or so, much internal stress in deciding how best to maintain the façade of a business-as-usual energy strategy. It is the IEA's own annual publication "World Energy Outlook" that each year shows projected global oil consumption and depletion fast tracking upward to 100 million barrels per day and another 60 million barrels per day of gas in oil equivalent by 2020. The consequent CO2 emissions, therefore, are shown to rise to just under 40 billion tonnes per year. Business as usual indeed. The whole notion is absurd! Moreover, in the last 30 days, after 30 years, they have changed direction. Better late than never!

In other words, the IEA has done a volte-face in November 2005. But again, wait for the final note: as though to contradict the "peal oil" geologists, the IEA states "there is still enough oil—enough to last another 30 years—all it will need is $17 trillion dollars of investment in production and plant infrastructure". Yes: 17,000 billion dollars over 30 years or 500 billion dollars per year. Oh! I forgot. The IEA also said that most (almost all) of this onus for production increase would have to come from OPEC. It didn't explain why there is apparently little hope or expectation that investment, no matter how massive, in North America, Europe or in deep sea drilling will make any meaningful difference. Therefore, the "lots of oil" is "lots of oil" except in a few places. One should not expect politicians to exhort more and more spending on oil exploration in old producing territories. Few things are as nonproductive as a once depleted oil field. Who will invest in the Brooklyn Bridge?

The most telling point I leave toward the end. It is that if you carefully read the statements made by those wishing to put an optimistic spin; oftentimes they confirm rather than contradict the statements made by "peak oil" analysts. For example, the IEA statement "there is oil to last for another 30 years" is hardly different from the peak oil thesis that oil will be extractable for at least another 30 to 40 years but it will not increase, but rather only decrease in relation to demand, falling short each year in meeting that demand. The shortfall will create a psychology that will drive prices into a cocked hat of spiral and uncertainty. We will either ramp up in time with tar sands, shale and nonrenewables or we will face a sharp increase in the "index of misery" as food, fibre and mobility prices escalate wildly. Concurrently, if renewables lose out in development priority to tar sands, Arctic pipelines and more and more coal, you can expect the projected 40 billion tonnes of CO2 to surge upward by a commensurate greater amount. There are other negative possibilities, of course. One example is the case where governments use renewable energy cash flow where it is working well to subsidize continued use of one or another of the fossil fuels, etc.

Yes, there is the tantalizing prospect of "clean coal". But, what does it mean? Coal can be cleaned, of course. It can be washed, scrubbed of its particulates and reduced in its sulfur emissions, etc., but to hype "clean coal" as being rid of its necessity to emit carbon dioxide in the burning of it, is to return to the nonsense alchemy of the high Middle Ages. To burn coal in a modern power plant is to combine carbon and oxygen in prodigious amounts. A coal plant of 1000MW producing electricity, let's say, at 80% capacity factor, will discharge about 7 million tonnes per year of CO2 into the atmosphere. To suggest that this CO2 can somehow be all sequestered, avoided or stored away somewhere at that grand scale month after month, year after year, is to hype the most outrageous nonsense. Without oxygen meeting carbon—no combustion and no steam.

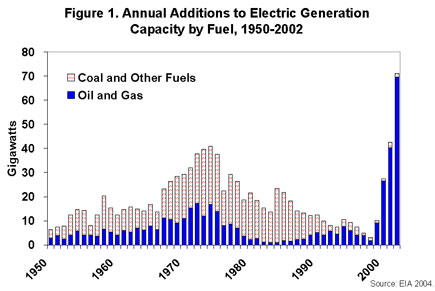

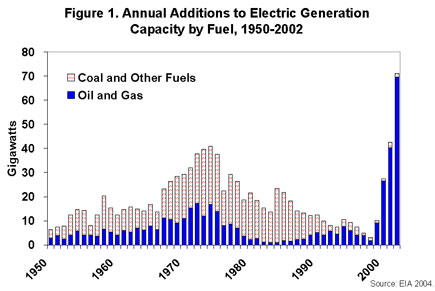

And, of course, natural gas combustion discharges carbon dioxide as well—at about 60 percent the rate of coal. That is not the only point. Natural gas is in much shorter supply, especially in North America, and its depletion rate on this continent is already making itself felt! Natural gas prices have tripled (+300%) in the past three years! The effect on home heating costs and industrial processing is drastic in its impact. The implications for fertilizer production and costs are severe enough to cause 100% price increases to western farmers. The politics of natural gas can be summarized as follows. All local clean air lobbies, and many environmental lobbies, favour natural gas over coal. However, those who are concerned with "sustainability" over the long run, favor coal over gas. Many lobbied for natural gas, not only for home heating where it was obviously to be favoured but also as a preference over hydro for electricity generation. In the latter case, it is not at all to be preferred, except for peak hour relief. Yet, repeatedly, in the 1990s to 2003, gas was promoted and installed in more than 90% of all new electricity-generating plants in North America. As a direct result, in at least three provinces in Canada, hydro development was poor mouthed and postponed, while we celebrated "an environmental victory" of gas installation. It was a mass phenomenon, like lemmings moving to the sea and their own demise. The shortsightedness and irresponsibility when shown in pictorial graph(a) is stunning. But, who will be called to account??

These events were a direct "defeat" for sustainability, if truth be known. The decade is only half over and already we are looking rather nervously at multi-billion dollar Arctic gas pipelines and multi-hundred billion dollar LNG terminals and ships to bring Mideastern, North African and Russian gas to North American shores because the decision makers have been so careless. That is where the politics of the 21st Century energy provenance seems to have taken us these past five short years.

Ironic this is too, because 48 years ago the Diefenbaker government enacted policy that established a National Energy Board. It was empowered to grant or withhold licences for natural gas export, unless it could be demonstrated that the depletion for export purposes was not to be allowed except in amounts that were surplus to domestic requirements of the next 20 years. That was all changed in 1990 after 30 years of successful stewardship. It was replaced by the current system, now 15 years old. That is by the politics that have recently dictated that gas production and exports shall be ratcheted up without regard for domestic needs. The cynic will be excused for noting the energy clauses of the Free Trade Agreement do not force Canada to increase exports of oil and gas to the US. What they require is that those exports cannot be reduced from the levels of preceding year(s). There is a difference. The onus is entirely ours. It is simply not right to blame Americans for decisions in Canada and the aimless policy drift that allows ratcheting. It is made-in-Canada policy. It was not made during the administrations of Messrs. Diefenbaker, Pearson or Trudeau. So two guesses as to when the National Energy Board process on gas exports was abolished.

To those who argue that without those energy resource clauses, the US would not have signed the Trade Agreement, I point out that Mexico very specifically declined from signing that Agreement until those energy clauses were removed. They were removed—they then signed on—and so did the US. (If they had softwood lumber and Mad Cows, would they be treated differently than we were last year?) After all, the notion that a nation must be obliged to buy products or resources it doesn't want or need is absurd. It is equally absurd that a nation must sell off resources at a rate any faster than it wishes to extract or deplete. Almost half of the American population would like very much to build up their own energy options and preferably base their energy policy more on sustainable modalities; and reduce, at long last, their perceived over dependency on foreign oil, especially Middle East oil. This is a growing consensus among many members of Congress today. They must wonder when they see the other half of the population supporting those who appear to demand that OPEC and other countries spend and invest heavily to increase production in order to deplete more rapidly that very resource they feel they are already exploiting too heavily and too quickly. And what would be the result of increasing production—to sell 20% more volume at 20% lower price? Better to leave it in the ground an extra few years. It might appreciate in value. So goes, and so will continue to revolve, the politics of fossil fuel energy during the first two decades of the 21st Century.

The essence of the energy and environmental policy dilemma is not whether we must change policy direction but rather how soon can we start. We must put practical renewable energy capacity in place. There are two reasons why we must insist that no more time should be wasted as has been wasted this entire past decade. Some may argue that almost half of world oil reserves are now depleted while optimists (forced or otherwise) may insist that almost half of ultimate reserves remain to be exploited.

They both happen to be right. That is not the point. Does it really matter so much if the cup is half full or half empty? The far, far more important thing we must do is to accept the real possibility that beyond a certain point, global capacity to produce will decline and fail to meet demand. Prices will soar as supply becomes erratic and undependable month to month. We will either be ready with a rational plan of practical alternatives (that are also non-greenhouse gas emitting) or we will witness a deterioration in environmental balances and sustainability, even while misery escalates in the face of decline in the production of the necessities of life. Is it rational to ration and conserve energy or is it "merely a personal virtue but of no relevance to public policy?" (as was recently uttered by senior White House official). Or was it the Mad Hatter or the March Hare who said this? No matter. Perhaps it is up to us if these next two decades are to become the best of times instead of the very worst of times. Possibly that is oversimplifying the possible scenarios. It may be that resource constraints, limits and realities in the face of a global population growing eventually to 8 billion and beyond, will outpace the best of human ingenuity and technological innovation and defeat the best of human rational impulses and decent determination to do ultimately the right thing.

However, I like many others, choose in spite of the foregoing, to be optimistic. The ethical teachings of Greco-Roman civilization and the Judeo-Christian tradition lead us to the guiding principle of moderation in all things: moderation as being the basis of right action. This may motivate us, even if late in the day, to finally do the right thing. The consequence of doing otherwise does not bear thinking about. The very scale of human consumption and impact has, in the 21st Century, caught up with the vastness of the scale of Planet Earth and her "vast resources". Now what?